December 22, 2021

1. Inflation Is Now Increasing

Inflation has been in the news recently. This month’s inflation reading is expected to indicate that prices have moved up over 6% since last year, the highest rate since 1991. (https://finance.yahoo.com/news/consumer-price-index-what-to-know-this-week-190934215.html)

2. Powell as an Inflation Fighter

Many articles on Powell’s recent reappointment focused on the need to battle inflation, as indicated by headline: “Biden Picks Jerome Powell to Lead the Fed for a Second Term as the US Battles Covid and Inflation.”

I believe that the Fed’s efforts to fight excessive inflation are important. They should strive to keep inflation from getting out control as it did in the 1970s. But I also believe the ultimate goal of the Fed and the policy makers around the world will not be extremely low inflation, such as the low levels of the 2008 to 2018 period - but instead a moderate level of inflation. A level of 2 to 4 percent might be more realistic for a protracted period.

3. Global Economies Have Recently Confronted Something Worse than Inflation: Deflation

After the global financial crisis in 2008/9, inflation declined so much that the major concern among central banks around the world was not inflation but deflation – where prices decline over time. While this sounds good, it tends to harm economic growth. When consumers get a sense that prices will be lower in the future, they put off purchase to wait for better prices. When they do that, production declines and economic growth slows. Here is an article about deflation and I have included (below) the key passage (https://www.thebalance.com/what-is-deflation-definition-causes-and-why-it-s-bad-3306169):

· Deflation slows economic growth. As prices fall, people put off purchases. They hope they can get a better deal later. You've probably experienced this yourself when thinking about getting a new cell phone, iPad, or TV. You might wait until next year to get this year's model for less.

· This puts pressure on manufacturers to constantly lower prices and develop new products. That's good for consumers like you. But constant cost-cutting means lower wages and less investment spending.

For much of the 10-plus years after the global financial crisis, central banks sought to induce inflation and the US Federal Reserve set an inflation target of 2%, annually, which it struggled to achieve. Here is a quote from one of many articles on the topic from 2015 (https://www.cnbc.com/2015/10/13/the-us-is-closer-to-deflation-than-you-think.html.):

· Nonvoting member James Bullard, who heads the St. Louis Fed, is among those pushing for a rate increase, as he believes policy has helped make “cumulative progress toward committee goals,” as he said in a speech Tuesday.

· Fed Gov. Lael Brainard, who does have a vote on the FOMC, countered that deflationary pressures argue against an increase.

· Our economy has made good progress toward full employment, but sluggish wage growth suggests there is some room to go, and inflation has remained persistently below our target,” Brainard said in a speech Monday. “With equilibrium real interest rates likely to remain low for some time and policy options that are more limited if conditions deteriorate than if they accelerate, risk management considerations counsel a stance of waiting to see if the risks to the outlook diminish.

4. How Inflation Might Be Used to Address Our High Levels of Debt

Inflation is likely to be higher over the coming years not only because of Covid stimulus, infrastructure, and climate spending, but also because higher inflation addresses a more fundamental problem the US and other countries have. The article below requires a subscription, but I have included key sections below (https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2021-11-16/greenspan-s-bond-yield-conundrum-has-returned-to-haunt-markets):

The writer, John Authers, does a good job of laying out a few key points:

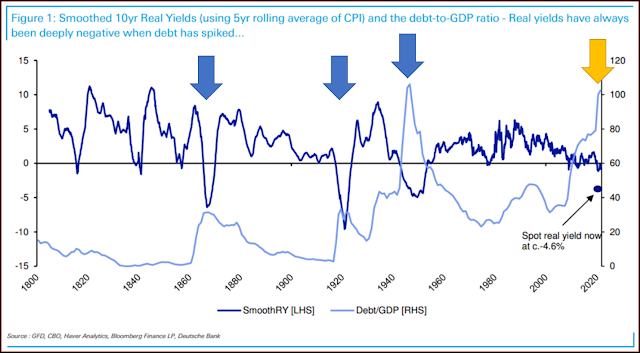

- This chart is from Deutsche Bank’s indefatigable financial historian Jim Reid and goes back to 1800. It compares debt/GDP ratio with real yields defined as the prevailing 10-year rate subtracting the five-year rolling average of inflation:

[Note from JHansen: The above chart focuses on just the US. I have added three big blue arrows to indicate the three earlier periods of low real yields (dark blue line labelled “SmoothRY”) and high Debt-to-GDP ratios (light blue line), plus, in yellow, the current period. The key thing to note is the high debt-to-GDP levels under the four arrows. Generally speaking, high levels are bad.]

· On this view, real yields have been as low as this three times before in the last 200 years: during the U.S. Civil War, the Great Depression, and finally in the aftermath of the Second World War. In all cases, for obvious reasons, debt spiked. That has happened again [yellow arrow, JHansen], although not for reasons as horrific as a war or a depression.

· The low real yields associated with the Second World War came during a period of explicit “financial repression” when the government held them [real bond yields] low to make it easier to pay off the debts incurred to finance the conflict, and the Fed had to surrender its independence for a matter of years. The Reid hypothesis is that with another epic debt pile to pay off, another episode of financial repression lies in our future. He also suggests that a combination of inflation (to reduce the value of the debt) and repressed yields (to make it cheaper to service) mean that real yields will stay negative for the rest of his career, and that this unenticing option is superior to the alternatives:

· Financial repression has always won out. The previous debt spikes occurred around the Civil War, WWI and WWII. This latest climb had been steadier (but substantial) until Covid, which may explain why real yields have steadily but consistently declined. However, the economic response to Covid has been more akin to a war time response, with debt and spot real yields both spiking in opposite directions just like that seen around and after the wars discussed above.

· [W]ithout financial repression, real yields would likely be consistently positive at the moment given the weight of global debt. But given this global debt pile, that would strongly increase the probability of financial crises across the world. So the risk to my “rest of my career” view is that something happens in the years ahead that prevents the authorities using financial repression. If this occurs then the global financial crisis may look like a dress rehearsal for a much bigger event. So the incentives for the authorities are there.

· Beyond that, a world of financial repression would continue to be a world of TINA, where we are left grudgingly to buy stocks because There Is No Alternative [TINA = There is no alternative. Low yields mean that bonds deliver lower returns to investors. - JHansen]. It’s not appealing, and arguably it’s not really capitalism, but it might be the best way forward. It’s also a worryingly good explanation for the continued low long yields.“

Low “real yields” means that the yield on bonds is low compared to the inflation rate, and “long yields” are yields on long term bonds.

"Financial repression" is known to those at the Fed. Here is quote from a Fed paper on the topic (https://www.richmondfed.org/publications/research/econ_focus/2021/q1/economic_history):

A Tool of Debt Liquidation: In many countries during 1945-1980, financial repression effectively lowered the real returns to government debt holders and helped governments reduce their debt-to-GDP ratios, according to research by Reinhart and M. Belen Sbrancia of the IMF. Based on their calculations, real returns on government debt were negative in many countries over 1945-1980. The real returns to bond holders averaged -0.3 percent in the United States, and real returns were even lower on the bonds of those European governments that had been particularly ardent practitioners of financial repression, coming in at -6.6 percent in France and -4.6 percent in Italy. ... Ever since McKinnon and Shaw, financial repression has been associated with inflation...

Given this discussion, we might expect 1) bond yields and interest rates to increase enough to introduce greater sensitivity to stock valuations over the short term and improve only slightly the long-term return to some bond sectors, 2) interest rates still low enough to encourage economic growth despite there being elevated inflation. 3) some upward pressure on stock prices because stocks have pricing power and can pass on any their higher costs to their customers, If this does turn out to be the case, investing in stocks will be most beneficial because of TINA – there is no alternative.

Here is another piece about the a force that will keep long-term bond yields low, even with inflation. This is from a Bloomberg article: "A Global Savings Glut Is Set to Anchor Treasury Yields Below 2%" [2021-12-22 01:01:54.967 GMT] By Garfield Reynolds and Michael MacKenzie.

- (Bloomberg) -- Anyone gearing up for bond yields to surge in 2022 should think again. A global glut of saved cash has the potential to restrain an increase in rates, even as central banks dial back their pandemic stimulus. The strength of demand for bonds even in the face of deeply negative real returns underpins the broad consensus that 2% may act as a ceiling for U.S. 10-year yields in the coming year.

- But strategists expect the advance to be gradual and top out in negative territory on an inflation-adjusted basis. Fed Chair Jerome Powell highlighted the role of deep-pocketed foreign investors in repressing longer-dated yields just after this month’s final policy meeting for 2021.

5. One Final Opinion: Expect to “Muddle Through” as Opposed to Expecting a “Crisis to be a Cleanser”

When I started in the investment business years ago, I thought of the economic and stock market cycles as periodic waves of getting rid of the old, inefficient aspects of the economy and allowing new ones to grow. While this rhythm does indeed take place, the periodic purges and sprouting new ways have never been as big as I thought they should have been. It is true that when the housing crisis started in 2007, it seemed that financial leverage and novel ways of packaging investments had become excesses before the crash of 2008, and these excesses were addressed.

When the dot-com bubble inflated in the late 1990s, there was much talk about the extreme valuations of companies with little or no revenue, and the subsequent bust of the bubble addressed those excesses. After the run-away inflation of the 1970s, it was clear that inflation had to be addresses, and Paul Volker increased interest rates and inflation was tamed by the early 1980s.

To be sure, these were major adjustments, but it surprised me at those times just how much of the economy continued and absorbed these changes. It surprised me how much stayed the same.

I think I had in mind the experience of the Great Depression when the stock market dropped about 80-plus percent, the economy in the 1930 was indeed a shambles, and it took years (and probably WWII) to get back on its feet. After that collapse, the economy and the country were completely different in many ways. I think I was expecting change of similar magnitude. But now, I realize that this expectation was unrealistic.

The economic collapse after the 1929 stock market crash was different. At the time the Fed and the government responded with a tough-love approach. There were government and business leaders who expected and maybe even welcomed a cleansing crisis that would abolish the excesses and provide fertile soil for new economic growth. This is a quote from a very interesting Federal Reserve history piece (https://www.federalreservehistory.org/essays/great-depression):

· A few governors subscribed to an extreme version of the real-bills doctrine labeled “liquidationist.” This doctrine indicated that during financial panics, central banks should stand aside so that troubled financial institutions would fail. This pruning of weak institutions would accelerate the evolution of a healthier economic system. Herbert Hoover’s secretary of treasury, Andrew Mellon, who served on the Federal Reserve Board, advocated this approach.

However, as the article indicates, this view is now considered by the Fed to be a mistake. Instead, during a crisis the Fed should be very benevolent so the economy does not collapse and gets back to growth quickly – economic growth addresses many problems. One need only look at the response to the Covid crisis to see that this mindset still prevails at the Fed and in our broader government, which have been excruciatingly benevolent. But the Fed has concluded, rightly I believe, that addressing the subsequent excesses resulting from benevolence when the economy is stronger is much better than not being benevolent during a crisis.

This means that we will muddle through each crisis and muddle through the effects of the remedies used to prevent economic collapse during each crisis. At present, this means addressing inflation while promoting economic growth and allowing the debt level to shrink in proportion to the growing economy.

I expect the Fed to allow the economy to run “hot,” which means that it will encourage economic growth and allow a moderate level of inflation to take place. Stocks will be likely be the main investment that produces a strong return in these future conditions. Thus, after an initial period of recalibration and potential decline, I expect stocks and to be influenced by the natural cycles of resilience.

I always pay attention to what Jeremy Grantham says. He may be right about a big decline that results in lower stock valuations. But even during the collapse of the internet bubble in the early 2000s, the natural cycles of resilience still allowed the MRI-based process to generate good returns. The same was true in the 1970s with its high inflation and the 1980s when inflation was fought. The same was true before and after the stock market peak in 1929. I expect our portfolios to do well in the environment described above and in other environments that are used to muddle through. The natural cycles persist.

Again, the implication for us is to get out of the stock market when it is vulnerable and to be ready to participate later in the growing economy, to earn high returns in our portfolios, and to keep well ahead of inflation when markets are resilient.

----------